Non-smooth Systems

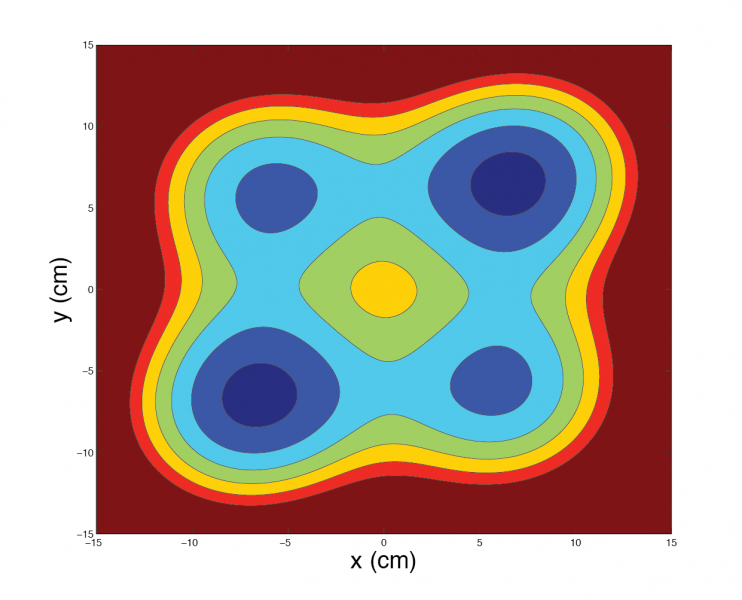

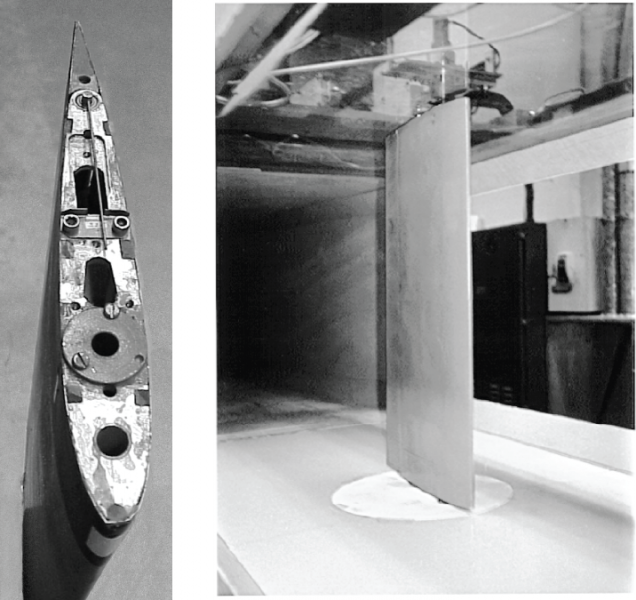

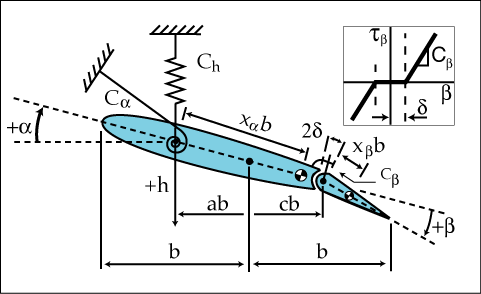

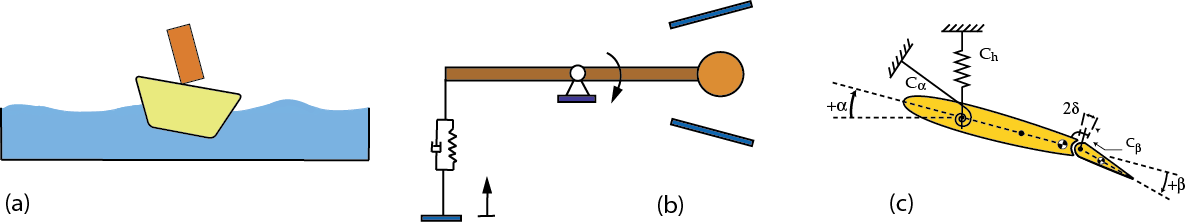

Many dynamical systems (especially mechanical) have discrete non-smooth characteristics. A good number of such systems have been studied in the nonlinear dynamics group here at Duke. One of the motivations for this work is that impacting systems often exhibit limited fatigue life. Non-smooth systems are capable of exhibiting behavior not found in smooth systems, e.g., grazing bifurcations. The systems below have a non-smooth stiffness characteristic:

Some other examples are show here:

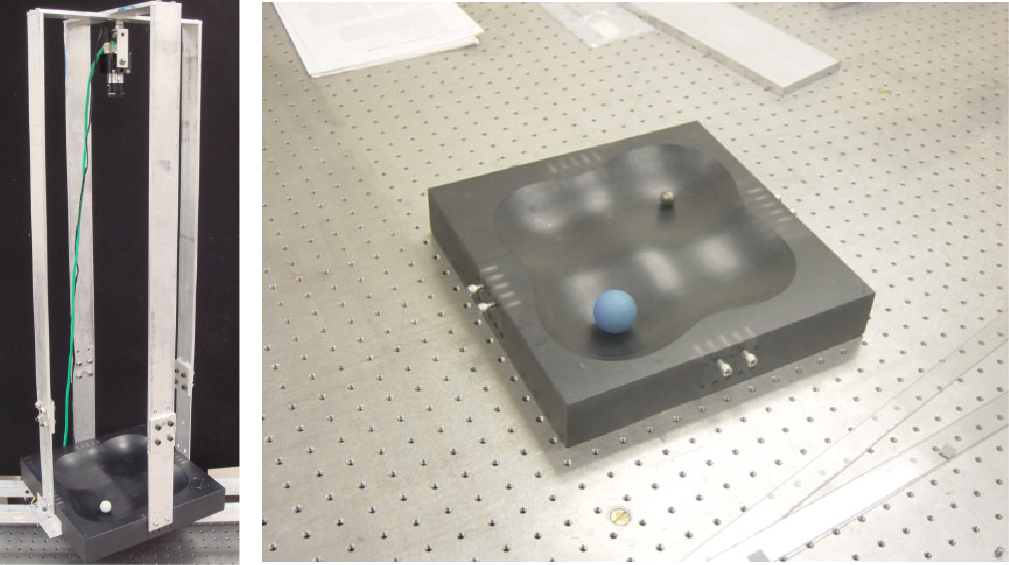

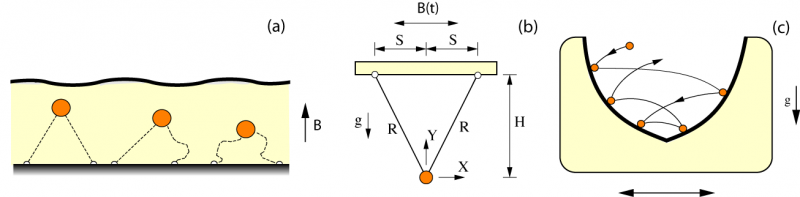

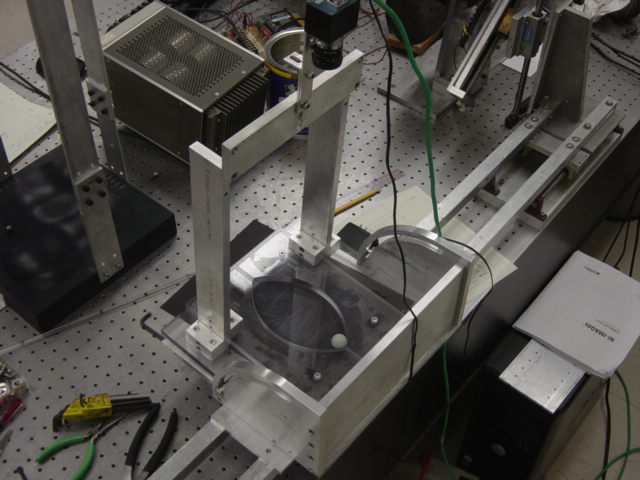

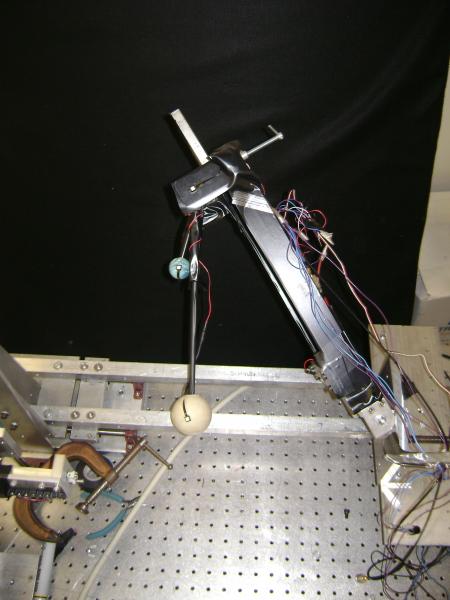

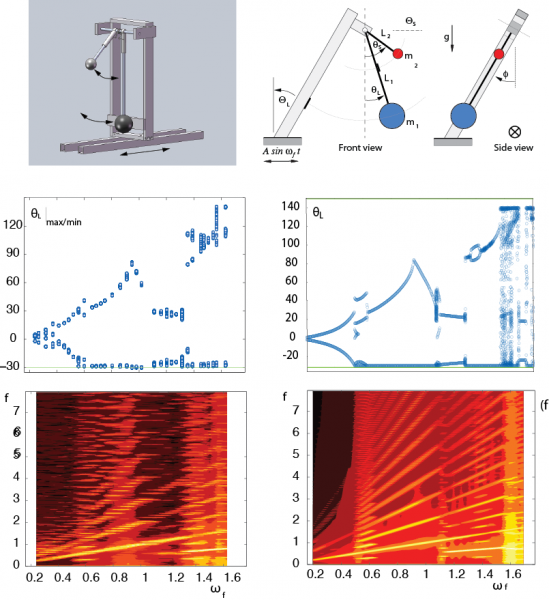

Another example is a double-pendulum impacting system:

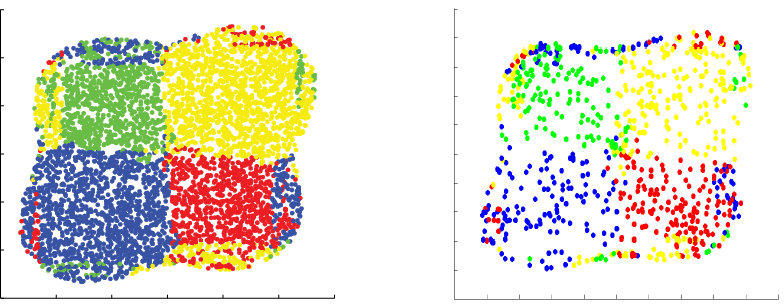

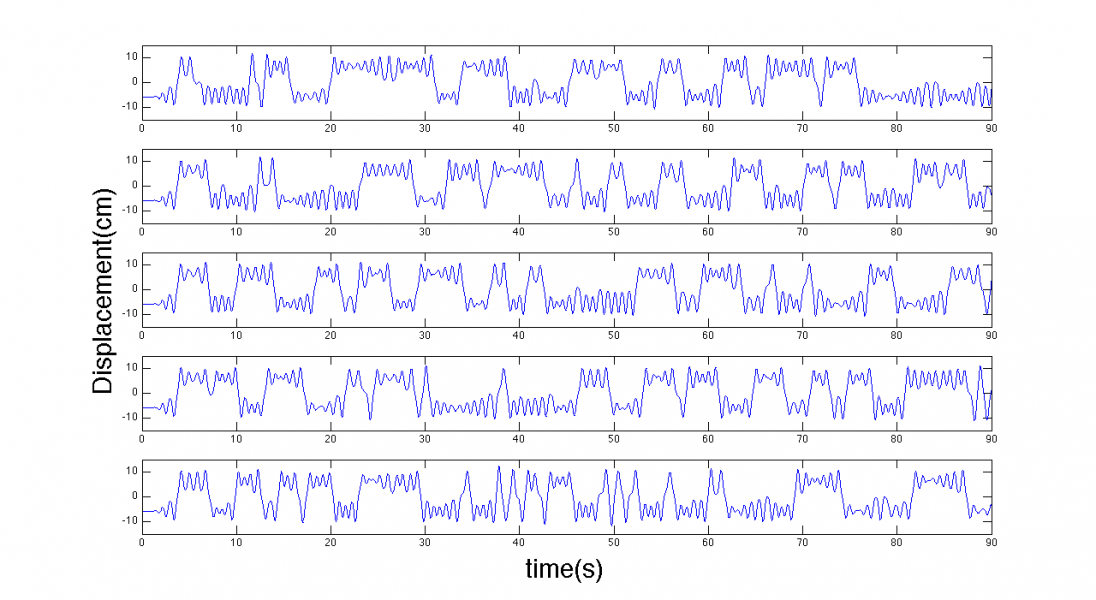

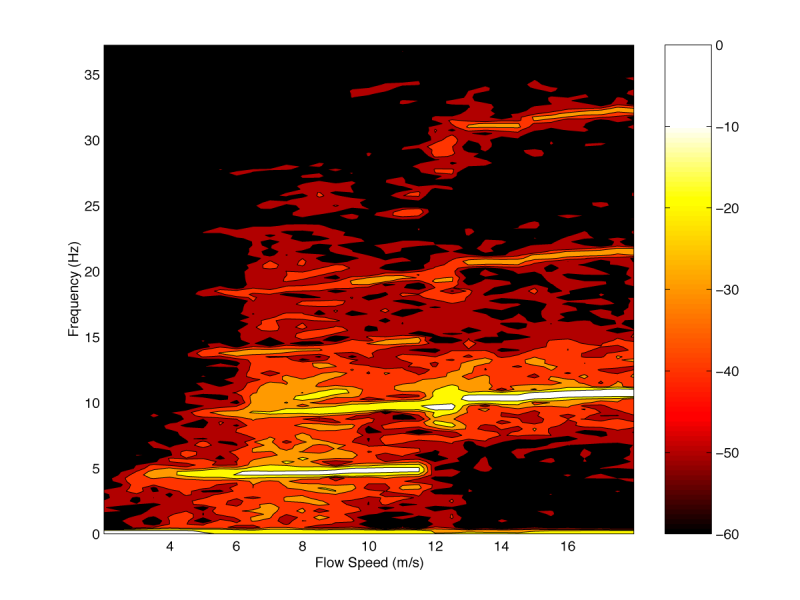

Simulations and experimental data compare very favorably, not just for specific parameter values, but across a broad range (bifurcation diagram and spectragrams). Experimental data on the left, numerical simulation on the right:

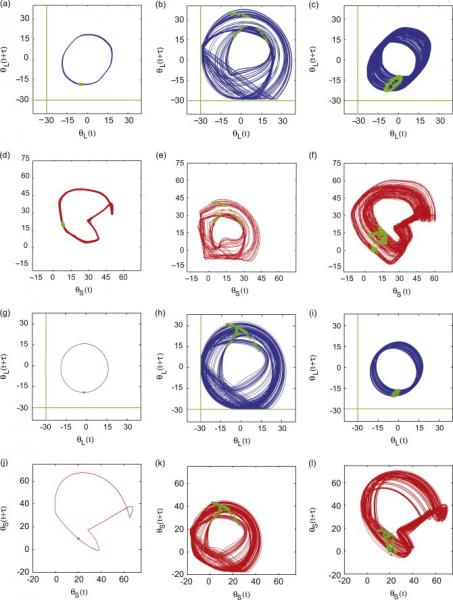

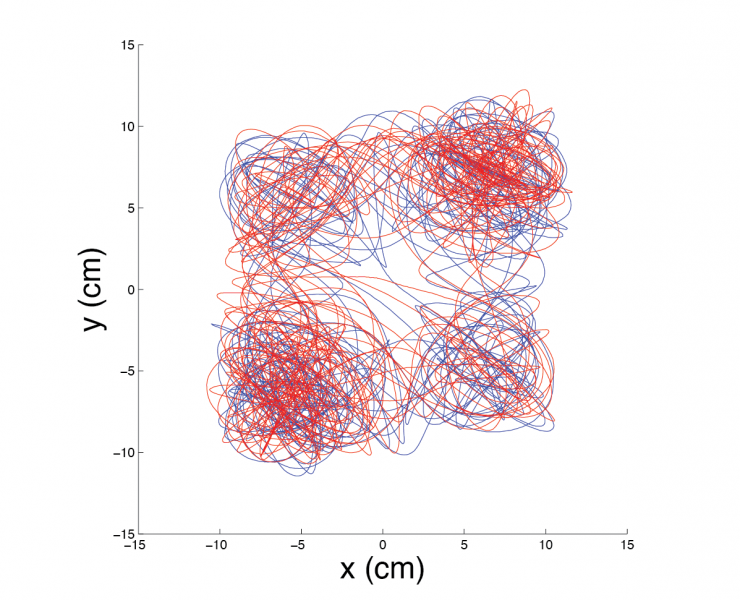

The response at given frequencies can be quite different. For example, below is shown both numerical and experimental data in terms of pseudo-phase projections and Poincaré points (in green) superimposed. (a) - (f) Experimental, (a) and (d) ωf = 1.43, (b) and (e) ωf = 0.58, (c) and (d) ωf=1.51. (g)–(l) Numerical, (g) and (j) ωf=1.415, (h) and (k) ωf=0.5719, (i) and (l) ωf = 1.43.